Dear Curious Minds,

It’s newsletter Monday. If you’ve been here a while, you know I dig deep into my personal stories. I’m perhaps raising that bar higher as I’m digging deeper than probably feels wise. You see, many of you know me professionally, and it pains me to reflect on some of my stupidest days. But I think there is something to be learnt in sharing that journey publicly. Who knows, maybe what feels like oversharing is enough to make one person to feel like ‘oh, I’m so glad I’m not the only one.’ That honestly will be enough for me. Thank you for being here, I appreciate you.

Pride Festival. Another year of rainbow flags, aroha in the air, and the ever-present promise of liberation.

Yet this time, under a sky that should’ve been lit up with vibrant celebration, we witnessed sour spectacle: two separate attacks have been reported with one at Te Atatu where 30 people linked to Destiny Church, penetrating a group of staff into a library with ironic battle cry of “Man Up”. It was more than just a slogan; it was a weapon, a thinly veiled assault on trans folk, an appropriation of the haka that mocked mana rather than honoured it, and a public sermon that turned religion into a cudgel against LGBTQIA+ communities.

There are a lot of complex and conflicting emotions being poured out from what happened here. Perhaps anger. Perhaps confusion. Perhaps sadness at how this aggressive posturing kept reappearing like a nasty recurring fever.

But let’s park that scene for a moment, because there’s more to the story. Their stunt, while jarring, is but a symptom of a deeper and more insidious pattern: the rising tide of far-right extremism, homophobia, and fascist rhetoric among young men globally.

Social and legal researchers around the world have pointed out online spaces have become hotbeds for the radicalisation of disillusioned youth, who find in these echo chambers a sense of belonging by scapegoating those who are simply different. In Aotearoa, the very same narrative played out on the Pride stage and “tough talk” theme got used to demonise entire communities. This mirrors broader global trends. That’s what makes Tamaki’s outburst less of a one-off sideshow and more of a local reflection of an international problem.

But anger, as we know, doesn’t come from nowhere. It’s forged in histories. Sometimes personal, sometimes collective. Always fanned by systems designed to pit us against each other. Nowhere is that more evident than in the stories of families grappling with intergenerational trauma. Let me share one:

A Story of War, Separation, and Survival

There was a teenage boy, forced by war to flee his family home and seek refuge in the countryside. He was prime target for the invading force because he was almost a ‘man’. Six more sleeps, he promised his six-year-old sister who cried as she clung to his arm. They’d all be together again by then. But the bombs and bullets had a different plan. Seventy-five years later to this day, he’s never seen any of them again.

That boy eventually got conscripted as the war dragged on for years. He survived atrocities that etched themselves into his psyche. Once the truce were signed, he married a similarly desperately impoverished and soft-spoken girl. He carried trauma he scarcely knew how to name. He worked tirelessly, drank, and worked some more, because nothing came easy and that was just the norm for most men around him. Under decades of militant dictatorship, he learned life was precarious; one wrong step could mean everything taken away again. It seemed stupid to him to let his guard down and be ‘soft’ to anyone because looking vulnerable was a risk he couldn’t afford.

He grew harsher towards his sons than his daughters, perhaps unconsciously echoing the patriarchal scripts he’d absorbed: “Stay strong, don’t be like a girl, show no mercy.” His eldest son bore the biggest brunt of corporal punishment and emotional whiplash. He, too, learned to keep his guard up, to see the world as a threat, to hold people at arm’s length. That son would go onto marry a woman the parents arranged for him, despise the life of subordination he subjected himself to by working for his father, and terrorise his children with his emotional and physical volatility.

Throughout this time, like many in this country post-war, church became centre stage in their life. They turned to religion, seeking structure and a moral code. Their diligence and hard-working nature were rewarded by respect and hierarchical status within the church congregation. They were also fed with something else: an echo of the same patriarchal rigidity that so often justifies the subjugation of women, the condemnation of queer folks, and the demonising of anyone who dares to live outside the lines. As the decades passed and several lucky breaks later, that family moved to a new country, found new churches, but the same old us versus them dogma persisted. “Our life in peace is under threat because those sinners,” was the easy scapegoat message.

Then something changed. The youngest generation were fatefully hypervigilant. How could they escape that skillset when they grew up with emotionally volatile and physically violent adults? They felt safer escaping into books, music, films than being around them. But they desperately wanted to understand why they were never enough to their parents. In their path of exploring that pain, they ended up in studies and jobs that were human-centred. They heard stories of diverse people living authentically and were inspired by art that celebrated identity rather than demonised it. Gradually, they found themselves questioning their own black-and-white thinking which had been the foundation of their upbringing. One by one, they peeled away from the hateful rhetoric, sometimes quietly, sometimes in open defiance.

I’m one of those children in the youngest generation. I was a bigot. I saw and spoke about the world through the lens of black and white thinking, supremacy, internalised misogyny and more shitty dogma than I can remember to name. I was wrong.

And it pains me to admit that. Because it reminds me many twisted things I said with such confidence. And for all the pain I caused to those who had to hear it.

But I have to say it. Not to seek forgiveness because it’s not my place to demand that from them. But in hopes I can push myself along this journey of further learning, in case I spiral again.

I felt threatened by the world because I learnt my vulnerability, my weirdness, my uncertainty were unacceptable. I had never learnt to love myself with those things intact. Instead, the “Real Man” in the family consistently showed burying the pain and lashing out at anything that felt too different was the way to go about life. When the two male figures in your family, each who are supposed to be the head of the household, set that cultural tone it takes a hell of an effort to break the generational trauma.

The Danger of Zero-Sum Thinking

This microcosm of our family story speaks to a broader phenomenon. Whether it is ethnicity, religion, or class, we see minority groups gravitating toward colonial power structures and fighting each other instead of uniting for common liberation. It’s zero-sum fallacy; If they gain, I must lose. That narrative is perpetuated by leaders who would rather see us divided. Why? Because divided communities are easier to conquer, easier to manipulate, easier to gaslight.

In the same vein, extremist ideologies feed off personal grievances. They tell disenfranchised young men that they’re losing “their rightful place.” They paint feminism, queer rights, and any form of equality as the enemy. Organisations like Human Rights Watch have long tracked the alarming rise of online radicalisation and homophobic narratives. The rhetoric might differ depending on the platform, but the result is the same: men, stoking their unresolved anger, blaming others for their pain.

Anger in Your Heart Is Valid; But No One Else Is Your Rehab

Here’s the core truth: anger itself isn’t the villain. Anger can be a catalyst for change. It can wake us up to injustices. I am a huge fan of angry nerds, and I don’t believe any of the social privileges I enjoy today would be here if it hadn’t been for those angry nerds in the past. What twists anger into something destructive is when we try to offload it onto communities who deserve safety, not blame.

No women, no queer person, no trans community, no minority group, should be subject to violence for men’s wounds. Healing demands introspection, therapy, peer support, and community networks that foster understanding rather than hostility. Dealing with trauma means asking for help and being open to transformation, even when it’s uncomfortable. Especially when it’s uncomfortable.

“Man up,” as this group uses it, is a cheap sell. It is an exhortation to dominate rather than feel. But let’s be clear: a real man can (and should) cry when his heart is heavy, ask for help when he’s lost, dance to a silly tune with the ones he loves, and stand up for vulnerable communities when they face oppression.

That is the kind of masculinity we need right now.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Name the Problem Clearly: Hateful rhetoric at Pride is not a fluke. It’s part of a global rise in far-right extremism and homophobia. Aotearoa is not exempt.

Push for Learning: Encourage open discussions about sexuality, gender identity, and mental health in schools, workplaces, and communities. Knowledge and increasing proximity inoculate against fear.

Support and Solidarity: Seek out organisations in Aotearoa like Rainbow Youth or mental health services such as 1737 for immediate support and resources.

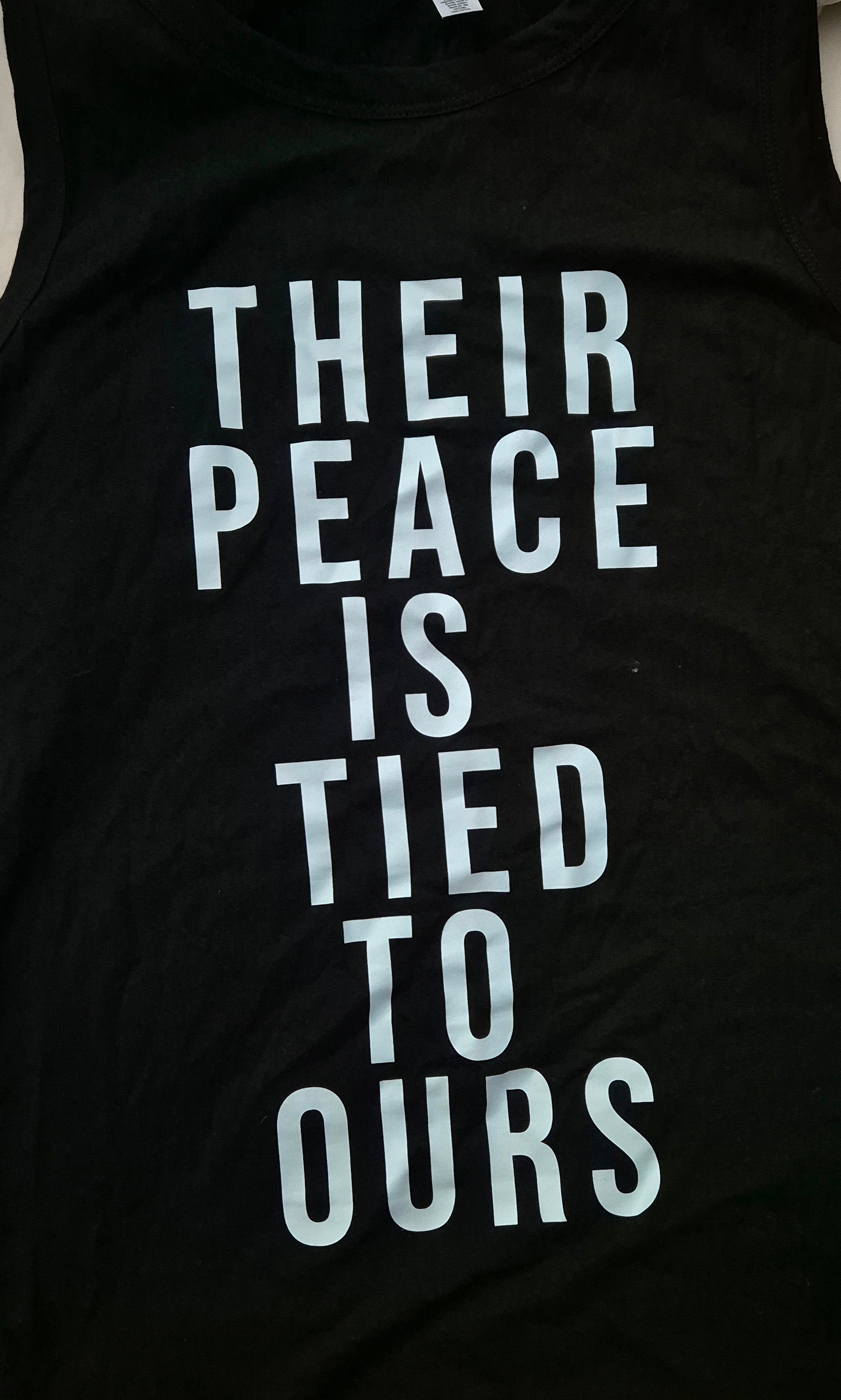

Disrupt Zero-Sum Thinking: Let’s confront the myth that if one marginalised community gains, the rest must lose. Collective liberation benefits everyone. Their peace is tied to ours.

Men, You Can Heal: Men, especially, need safe spaces. Therapy, support groups, and cultural practices can help process trauma and anger. The rest of the world cannot be random punching bag or rehab centre.

In Closing

As someone who’s walking the journey from bigotry to constant learning, let me say: you can choose to learn. Yes, it’s terrifying to admit we might be wrong. But there’s a surprising freedom in stepping off the hamster wheel of blame and fear. When we embrace our own vulnerability, we learn that being “soft” doesn’t mean being weak. It means being fully human.

And so, as the rainbow confetti from Pride settles onto the streets, there is an optimist in me that hopes anger can be a stepping stone to growth, but only if we claim responsibility for it. No one else owes us their bodies, identities, or celebrations to scapegoat or destroy.

Anger in your heart is valid. But as Matt & Sarah Brown famously put it she is not your rehab. They are not your rehab.

Let it be the mantra that guides us toward a more compassionate, accountable masculinity, and a society where everyone, regardless of who they love or how they identify, has the right to exist in peace.

References & Further Reading

Rainbow Youth – Aotearoa-based organisation providing support for queer and gender-diverse young people.

1737 – Free call or text service in New Zealand if you need to talk.

Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) – Tracking extremism and radicalisation globally.

Human Rights Watch – Global reports on discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people.