The Shame We Refuse to Name (Part 1 of 3)

Please stop the euphemisms

Dear Curious Minds,

Last week was the first time I didn’t post here on Entangled Curiosities for the entire week since I started on Substack last Oct. As with all deaths, perhaps more so because of grandpa’s dramatic and full life of 91 years, his death was a lot. And it wasn’t going to let my fingers quietly type away at my regular pace. For the most part, it was expected. But there was still some drama and emotions that I wish were fiction. This is part 1 of 3, unpacking some of those tangled, messy feelings. Thank you for being here, I appreciate you.

It’s been nearly two weeks since my grandfather died. But his death began days earlier, in a hospital corridor where medical professionals performed elaborate linguistic gymnastics to avoid saying what everyone already knew. Or what everyone should have had the chance to learn.

What I witnessed wasn’t a broken system failing to function but rather a system designed for efficiency metrics, successfully avoiding the time-intensive, staff-heavy reality of helping people die well. The tragedy isn’t that our healthcare is dysfunctional; it’s that it’s functioning exactly as intended by those who’ve spent decades restructuring it like a profit centre.

When Evidence Meets Ideology

For more than twenty years, I’ve been the designated medical translator for my family. So when my grandfather was admitted a few weeks ago, I did what I always do: I asked the hard questions early.

“What is his realistic prognosis? Should we be considering hospice arrangements? End-of-life pain management at home?”

The response was textbook deflection: “The patient and family will be involved if his condition comes to that stage. At this point, there are many more options for us to consider.”

A few days went by, and the cardiologist finally reviewed his file and deemed him unsuitable for invasive treatments. When I asked about prognosis and timeline, yet again explaining I didn’t need precision, just a ballpark so I could inform the wider family, I got: “That’s a good question. The team will pass that on to the specialist and get back to you.”

They never did.

Instead, nearly a week went past. I got a call from Geneva Healthcare about equipment delivery after his discharge. ‘That’s strange, we haven’t heard anything about his discharge plans.’ The caller explained it must be imminent as they only get notified when the discharge is nearly ready. Then the hospital pharmacist rang, trying to check if we could manage the long list of his new medications, and mentioned his “guarded prognosis” in passing. When I pressed about that wording, she didn’t want to “say the wrong thing” and that it would be best if I ask his doctor. This was Thursday afternoon. Friday morning, we discovered he was being discharged that day.

On Friday, we spent more than five hours in the transfer lounge waiting for discharge papers. When I finally received it, it mentioned palliative care involvement and that his case had been referred to the hospice. None of this had been mentioned to us during his admission. When I asked the staff for clarity, his doctor rang after a while: “The hospice team will call at some point. Your grandfather is medically stable, and that’s why we are sending him home. Nobody can know for sure, but palliative care involvement only means he isn’t suitable for invasive treatment, and pain management is the best option for him.”

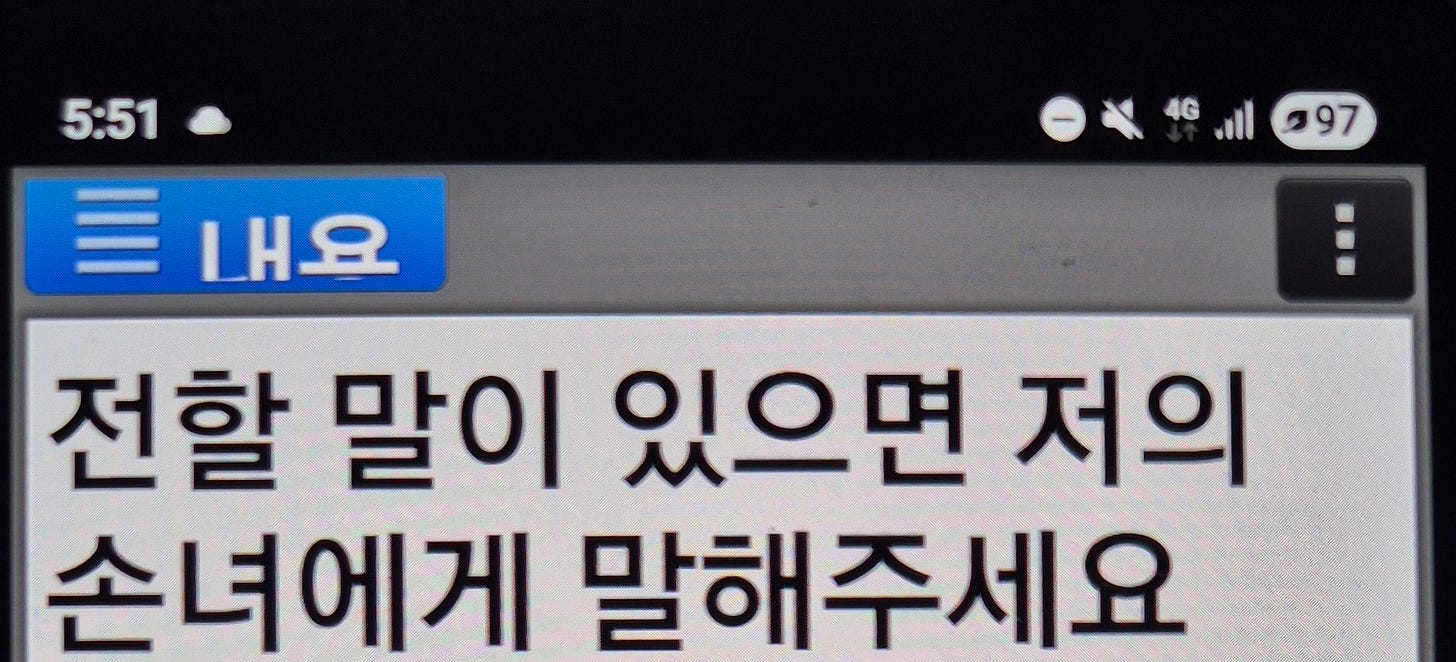

I wasn’t convinced. I assured them: “Clarity is kindness at this point. I really don’t need euphemism. I’ve had to explain a lot more traumatic news to my family, so please let me know if I need to contact family members who need to travel from overseas if he doesn’t have a lot of time left.”

But euphemism was all they had.

By Saturday evening, the very next day, his pain was unmanageable despite high-dose opiates. The paramedics who responded to our call provided more clarity in twenty minutes than we’d received from the entire two weeks at the hospital. They looked at his vitals, read his discharge papers, and expressed bewilderment: “Why was he discharged instead of being transferred to hospice?”.

Because the system was working exactly as designed. Maximum throughput, minimum time investment, essential conversations deferred to someone else’s budget line.

Because his file was sent to the hospice late Friday afternoon, he was not yet in the hospice system and technically in limbo. The paramedics worked around the clock the entire weekend, involving medical directors who could authorise the necessary painkillers, to ensure he received the best possible care until the hospice could take over on Monday.

When the hospice nurse finally called Monday morning, her anger was both validating and heartbreaking: “I’m so sorry your family has to go through this. My colleagues at the hospital really should know better. What they should have done was call us on Friday and ensure proper transfer. It makes me angry that doctors avoid talking about death and leave it to us. It’s not fair on you guys.”

The hospice doctor and nurse visited us first thing Tuesday morning, and fortunately, they could take him that afternoon. What we didn’t expect was for him to spend less than ten hours there and die that night. We are genuinely grateful for the exceptional level of care and empathy shown by St John and Harbour Hospice staff. He wasn’t in pain, and while he was conscious, he managed to say goodbye to a lot of people he loved and those who loved him.

But only after an unnecessarily chaotic and painful weekend that could have been avoided if we stopped pretending you can run end-of-life care like a quarterly earnings report.

The Pattern Repeats

This same pattern of evidence-denial disguised as dysfunction appears everywhere once you start looking for it.

Just a few days before my grandfather’s death, I attended a Dental for All campaign event. Someone asked the inevitable question: “How is the government going to pay for free dental care for everyone?”

The answer was as stark as it was ignored: we’re already paying.

The economic modelling is unambiguous. The social and financial costs of untreated or delayed oral healthcare range from $5 billion to $11 billion annually, far exceeding the $1.1 billion to $2 billion it would cost to provide universal dental services. Even with the most conservative estimates, the return on investment is 1.6 to 1. That’s not radical policy. That’s basic fiscal responsibility.

We have the data. We know this. The evidence is etched in government files, in Treasury analyses, and in peer-reviewed research. Yet we continue to cast votes for politicians and parties who dismiss evidence-based policy as “radical and idealistic” rather than recognising it as the economically sound investment it demonstrably is.

captured the same phenomenon, writing about Foreign Minister Winston Peters’ announcement on Palestine: “Our Foreign Minister is telling us that the years and months of detailed briefings from MFAT... amounted to little for him?”One of my other favourite writers on Substack,

, also identified the deeper grief beneath this pattern: “I am grieving, too, for what it says about us and how we have watched this unfold for months, for years, for decades, and still we are here, asking for our government to see humanity.”Evidence exists. Evidence gets ignored. We blame “dysfunction.” The real cause is a mismatch in ideological frameworks.

The Design, Not the Bug

Here’s what we keep missing. These aren’t systems failing to achieve their stated goals. They’re systems successfully achieving their actual design parameters.

When you structure public healthcare like a profit-hungry capitalist (with efficiency metrics, throughput targets, and quarterly restructuring cycles), you get precisely what such an enterprise optimises for: minimal time investment per “customer,” maximum volume processing, essential but unprofitable functions deferred to someone else’s balance sheet.

The hospital was obviously understaffed. Everyone was rushed, overworked, and trying to manage impossible caseloads. The junior doctor who made the prescription error for grandpa? Probably on their I-don’t-know-how-many-consecutive twelve-hour shift. The nurses juggling discharge paperwork while managing multiple patients? Operating at a capacity that perhaps would have been considered unsafe a decade ago.

This isn’t accidental. This is the result of years of deliberate budget cuts aimed at making public healthcare appear inefficient and dysfunctional. Starve the system, point to its failures, then suggest private alternatives as the solution. It’s neoliberalism 101, and we’re watching it happen to one of our most essential services.

We’ve systematically underfunded our public health system while offloading essential end-of-life care to the charitable sector. Creative accounting at its finest. We don’t pay through taxes for adequately resourced healthcare, but we expect charities to fundraise and beg for grants and philanthropic donations to provide the same services.

The cruel irony is that we’ve been convinced that the same quarterly profit logic that works for tech startups should somehow apply to the system caring for our most vulnerable moments. We’ve accepted that our publicly trained doctors and nurses, funded by decades of our tax contributions, should operate within structures designed for shareholder returns rather than human dignity.

After decades of paying into this system, we deserve the time and space to die well, not the efficiency metrics of a restructuring consultancy.

What Changes When We Name the Real Problem

The emotion that hit me hardest after my grandfather’s death wasn’t sadness; I’d been preparing for that. It was shame. But not shame directed at the individual doctors and nurses who were clearly doing their best within impossible constraints.

The shame I felt was systemic. The shame of recognising that we’re not failing to fix broken systems. We’re successfully operating systems designed for outcomes different from what we claim to want. The shame that I continue to contribute to it, and will continue to depend on it.

Because here’s what shame looks like when properly directed: not the individual kind that makes us spiral into self-blame and paralysis, but the systemic kind that says “this is working exactly as intended by neoliberal design, and we should be embarrassed about accepting the pretence that you can run public healthcare like a capitalist profit centre.”

My grandfather’s death taught me that euphemisms are not kindness. They’re cruelty disguised as politeness. And our collective refusal to name the real problem, that we’re applying the wrong framework entirely, isn’t protecting anyone. It’s just making everything worse.

We are, collectively, choosing to ignore evidence when it’s politically inconvenient. And then feeling ashamed about the predictable consequences of that choice.

But naming the real problem feels like the first step towards something better. Because once we stop mistaking deliberate design for accidental dysfunction, we can start having conversations about what we actually want our systems to optimise for.

So here’s my small act of resistance: I’m naming the design. We are easier to exploit when we feel helpless and stupid. So we are fed so much fuel against collective resistance and solidarity by design. I’m refusing the euphemisms about “broken” systems that are working exactly as intended. And I am betting others, at least those of you here with curious minds, are feeling this same energy: this restless, uncomfortable recognition that we’re collectively choosing to apply the wrong framework to the things that matter most.

Fixing broken systems sounds too vague, just like those euphemisms I got at the hospital. But one thing is clear for me, at least. I am finally getting angry enough about applying profit logic to human dignity that we refuse to pretend it’s anything other than what it is: a stupid fundamental category error that we have the power to correct.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series exploring the emotions we’ve been trained to avoid, and why avoiding them might be precisely what’s keeping us stuck. Subscribe and stay tuned for more.

Entangled Curiosities is a reader-supported musing. I know it’s hard to commit to monthly subscriptions! But if you can afford it, your koha helps me take deep dives, plan engagement activities and advocacy campaigns. So it would mean a lot to me if you could support this mahi with a one-off virtual coffee, especially if you enjoyed this entangled feminist rage and grief.

I like that you've made your grim encounter with the hospital system in Aotearoa NZ a lesson in how our government is privatising a health system. (By stealth).

I've had a recent experience in an Auckland hospital and was funnelled rapidly through ED to Assessment and Diagnostic unit and home by staff including a "Flow Manager" - my first encounter with such a person.

Face to face encounters were polite and didn't seem too hurried; rather, efficient. Explanations were perfunctory and abbreviated. The impression was one of haste to move you through and out the other end of the line; ticked off as "done".

I cannot help but tie up in my mind the cool neoliberal approach to health care with the Seymour-sponsored Bill on Assisted Dying. Too silly?