The Yum Cha Paradox

The Ironic Mirrors We Refuse

Dear Curious Minds,

I’ve had a healthy number of new friends joining Entangled Curiosities over the weekend! Young and old, long-time supporter and newly found friend, I’m so humbled you are all here. If you are based in Tāmaki Makaurau, I hope you can come and join a bunch of us Sat 13 Sep for Aotearoa’s most epic Hikoi for Palestine. This march for humanity is a united call led by Palestinians and tangata whenua - supported by communities from all over Aotearoa, including a group of Korean New Zealanders like me who will be joining in. Follow @AotearoaforPal for all Bridge March updates and information. Share widely! Nau mai, haere mai e te whānau! Thank you for being here, I appreciate you!

Australia, bless your contradictory hearts.

This weekend's anti-immigrant protests offered us a masterclass in black comedy. Nothing quite captures the essence of human contradiction like watching protesters rail against immigrants before popping off to yum cha afterwards. It's the kind of cognitive dissonance that would make Leon Festinger weep into his research notes (happysad?).

You clearly missed Trevor Noah's memo: "You don't get to eat ethnic food if you complain about immigrants." But then again, irony has never been particularly good at reading the room.

When Irony Turns Deadly

But while we were busy judging and laughing at Australia's dim sum hypocrisy, the weekend delivered something far more sinister. In Indonesia, Affan Kurniawan, a young Grab driver was brutally killed on Thursday by an armoured police vehicle which saw the world’s fourth most populous country see tension soaring in protest.

A few days leading up to this, Indonesian politicians were literally dancing. Fresh from voting themselves a large pay rise in the form of a ‘housing allowance’ that was ten times more than Jakarta’s minimum wage, while their citizens struggle with wages that barely cover basic necessities, they were caught on camera celebrating. The optics were so staggeringly tone-deaf that the entire country erupted in fury. If you ask me, I don’t think takes a lot for us Kiwis to imagine how infuriating this would be should the same scene unfold in the beehive.

Affan was just trying to make a living in a gig economy that pays peanuts, while the politicians who shape the economic policies affecting millions just handed themselves windfalls. The contrast is obscene. A driver scraping together rupiah while lawmakers toast their latest bonus. The irony is no longer just uncomfortable. It's deadly.

The Psychology of Projection: Why We Hate What We Are

These contradictions led me to think about something far more uncomfortable than political hypocrisy. Because here's what psychology research tells us about the things that really get under our skin: they're often reflections of what we can't stand about ourselves.

Carl Jung called it the "shadow", those aspects of ourselves we've rejected or refuse to acknowledge. More recent research that I prefer spending time on backs up this uncomfortable truth. Studies on projection show that the traits we most vehemently criticise in others tend to be the ones we possess but haven't integrated or accepted in ourselves.

The classic study by Schimel et al (1999) argues that projection is a defence against anxiety about unwanted aspects of the self. Participants who scored high on measures of prejudice were significantly more likely to attribute those same prejudiced attitudes to others, even when presented with neutral information. We literally cannot see clearly when we're looking at our own reflection in someone else's behaviour.

But it gets a bit messier (and more interesting, for me anyway). Projection isn't just about the big, obvious stuff. It's the person who rails against "virtue signalling" whilst constantly posting about their own good deeds. It's the friend who criticises others for being "too sensitive" whilst being the first to take offence at gentle feedback. It's precisely when we're avoiding our own work that we notice laziness in others. (Ummm, I am definitely going to go get that blood test this week…)

The psychological function is actually quite clever, if brutal. By externalising what we can't bear to see in ourselves, we get to feel righteous instead of vulnerable. We get to be the hero fighting against the very thing we secretly fear we are. Call it emotional housekeeping. Except instead of cleaning, we're just shoving all the mess into someone else's yard over the fence and then complaining about how untidy they are.

This is why those yum cha protesters couldn't see the contradiction. Acknowledging their dependency on immigrant culture would have meant confronting their own complex relationship with belonging, with change, with their place in a shifting world. Much easier to rage against the mirror than look into it.

And it explains why proximity makes projection so much more intense. The closer someone is to us (e.g. culturally, socially, economically), the more precise the reflection becomes. Those Indonesian politicians dancing whilst their citizens struggle? They're not just celebrating pay rises. They're celebrating their distance from the very people they're supposed to represent. The projection isn't "those corrupt politicians over there"; it's "we're nothing like those people suffering down there."

The cruel mathematics of it all: the stronger our reaction to someone else's behaviour, the more likely we are to be seeing something uncomfortably familiar. The person whose selfishness absolutely infuriates you? Check your own recent choices. The colleague whose incompetence makes you rage? Might be worth examining what you've been avoiding in your own work.

It explains why those protesters felt so threatened by the very people whose culture they were consuming. The geographic, cultural, and economic proximity made the mirror impossible to ignore. You don't feel rejected by people whose acceptance you don't crave. Because you don't rage against systems you're not secretly worried you might need.

The Cruel Irony of Proximity

But here's where it gets personally almost too uncomfortable for me. Research on feedback and social distance reveals another harsh truth: the closer someone is to us, the harder it becomes to hold up that mirror. We're more likely to give direct, honest feedback to strangers than to our nearest and dearest. The stakes feel too high. The relationship too precious. The mirror too sharp.

Oh, wait….Which brings me to my own catastrophic spiral. What if I'm the yum cha protester in someone else's story? What if I'm the politician dancing while others struggle to survive?

What if there's some glaring contradiction in my life that everyone can see except me? Some way I'm benefiting from the very systems I critique, or perpetuating the patterns I claim to want to dismantle? Maybe it's the way I write about decolonisation from institutions that colonised my family's homeland. Maybe it's how I critique capitalism whilst building a business. Maybe it's smaller and more personal… the ways I ask for vulnerability whilst guarding my own.

The people closest to me can see these contradictions more clearly than I can. But love makes us kind. Proximity makes us careful. I will edit a version of me that fits the environment or people I care about, soften the observations, and swallow the feedback that might sting.

The Weight of Seeing Clearly

That young driver in Indonesia didn't have the luxury of cognitive dissonance. Neither do the millions of Indonesians watching their elected officials celebrate pay rises whilst they struggle to afford rice. The contradictions that feel abstract to those in power are lived realities for everyone else.

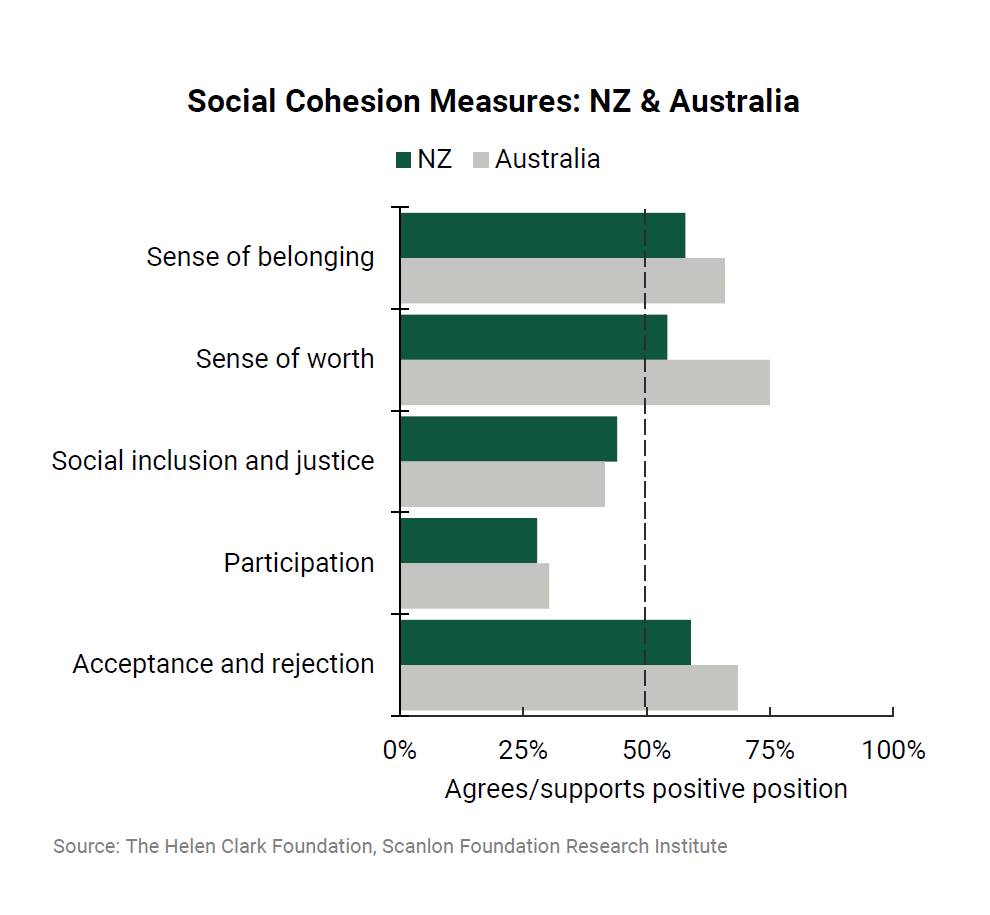

However, if we're honest about our own contradictions, we must also be honest about the broader ones. The Helen Clark Foundation's recent social cohesion report presented some genuinely confronting statistics for New Zealanders. We scored worse than Australia on every single metric they measured. Every single one.

But here's the statistic that felt most personal. When asked whether "immigrants make good citizens," only 51% of New Zealanders agreed. In Australia? 92%.

Think about what that actually means. Only half of us actively believe immigrants make good citizens. The other half either disagrees or remains unsure. In Australia, the country we like to think is way more racist than New Zealand, it's the complete inverse; only 8% don't actively agree that immigrants make good citizens.

We're not talking about a slight difference of opinion here. We're talking about a country where nearly half the population can't bring themselves to say that people who've chosen to make New Zealand their home, who work alongside us, whose children go to school with ours, make good citizens.

Meanwhile, we'll queue up for dumplings without a trace of irony.

The pattern held across every immigration question they asked. Only 56% of us think accepting immigrants from different countries makes New Zealand stronger, compared to 82% of Australians. Only 50% believe immigrants improve society, compared to 82% next door.

Many of us probably grabbed kebab or butter chicken this week. And that's perhaps the cruellest irony of all: the further you are from the consequences of systemic failures, the easier it becomes to ignore the contradictions. Whether it's politicians in Jakarta or those of us writing comfortably from Auckland, the more insulated you are by privilege, the less likely anyone is to hold up that uncomfortable mirror.

What Social Cohesion Looks Like When We Stop Pretending

Here's my attempt at untangling the question for us, especially those of us writing from positions of relative safety: What would social cohesion actually look like if we could openly embrace irony? Not just the comfortable kind that lets us mock others, but the harder kind that demands we examine ourselves?

What if we could hold mirrors for each other, gently, but clearly? What if we could name our projections before they calcify into hatred or policies that widen the gap between those dancing and those dying? What if proximity became a gift rather than a barrier to truth-telling?

My vision for social cohesion isn't about homogeneity nor eliminating our contradictions. I think it’s closer to developing enough humour and humility to owning our weird quirks and contradictions before they own us or worse, before they harm others. Perhaps it's about recognising that the Yum Cha protester and the dancing politician live within all of us, and choosing to nurture our accountability rather than our rage.

Affan was only 21. He deserved better than our collective cognitive dissonance. At the very least, we can stop dancing long enough to look in the mirror.

Entangled Curiosities is a reader-supported musing. I know it’s hard to commit to monthly subscriptions! But if you can afford it, your koha helps me take deep dives, plan engagement activities and advocacy campaigns. So it would mean a lot to me if you could support this mahi with a one-off virtual coffee, especially if you enjoyed this entangled feminist rage and grief.

What if the tension between surviving and striving to thrive quietly binds us to the very systems we seek to undo? What if this isn’t decolonisation at all, but a cycle of resistance that keeps us tethered to our rage, protesting endlessly, not because we are free, but because we are still trapped? Maybe we are all just small fish, swimming against the current, chasing liberation in waters designed to exhaust us.

Very thought provoking, thank you